- Maps

- Central Conflict

- Citizens' Committee of 1000

- Working Class

Canadian Army Service Corps trucks with fully armed soldiers and Lewis machine guns patrol the streets of Winnipeg, June 21, 1919

“ Special Police” hose down crowds gathered in front of Bank of Montreal building at Portage and Main, June 21, 1919

“ Special Police” with billy clubs on Main Street as street car burns, June 21, 1919

Mounted Police charge into crowd at William Avenue, June 21, 1919

Mounted Police charge into crowd at William Avenue, June 21, 1919

Bloody Saturday

“June 21st, one of the blackest chapters in Canadian history…” * On the morning of June 21, pro-strike veterans assembled in front of city h... Read More

No Need to Hunger, Western Labor News, 1919

Members of the Winnipeg Women’s Labor League preparing relief packages for families of Nova Scotia Coal miners on strike, c. 1925

Women’s Labor League Announcements, Western Labor News, June 3 and 21, 1919

The Women’s Labor League and the Labor Café (Royal Albert Arms Hotel)

Women's Labor League. The Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Labor League (WLL) provided essential leadership and support t... Read More

Telegram Building, 1903

The Telegram Building

This building housed the Winnipeg Telegram, a daily newspaper which – like the Free Press and Tribune – joined the Citizens’ Committee in co... Read More

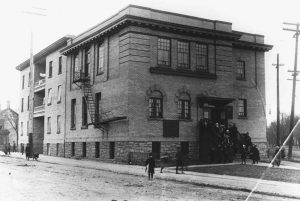

Winnipeg Board of Trade Building, Citizens’ Committee Headquarters, 1919

The Winnipeg Board of Trade Building (The Federal, or ‘Victory’ Building)

Today’s Federal Building stands on the site of the former Winnipeg Industrial Bureau Exposition Building, which housed the Winnipeg Board of... Read More

Walker Theatre Interior

Walker Theatre (Burton Cummings Theatre)

The spirit of the One Big Union and the Russian Revolution roared from the stage of the Walker Theatre on Sunday afternoon, December 22, 191... Read More

Fire Insurance Map showing Victoria Park along Red River, c.1919

Women and men at Victoria Park, June 1919

Labor Church Notice, Western Labor News, June 1919

RE Bray, leader of the pro-strike returned veterans, June 13, 1919

Victoria Park - “Liberty Park”

“Vast Assembly in Victoria Park”*. The James Street Labor Temple was too small to hold the thousands of strikers and their supporters wh... Read More

Meeting Room 10, James Street Labor Temple

James Street Labor Temple, Strike Committee Headquarters

James Street Labor Temple – Strike Headquarters

The James Street Labor Temple was the city hall of the labour movement. It was located on the city block where The Manitoba Museum now stand... Read More

Manitoba Club, c. 1920

Broadway and the Manitoba Club

The Broadway area was in transition in 1919. Many residents had already moved to Crescentwood, but the area was popular with wealthy doctors... Read More

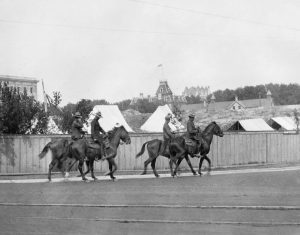

Police on horseback at Fort Osborne Barracks, 1919

Fort Osborne Barracks

On June 21 (Bloody Saturday) Mayor Gray met with General Ketchen at the Fort Osborne Barracks. Gray instructed Ketchen to assemble all avail... Read More

Military tents, Fort Osborne Barracks, with the Manitoba Legislative Building under construction in background, 1919

Manitoba Legislative Building

The present Manitoba Legislative Building was partially open in 1919, but most government business was still conducted in the old Legislatur... Read More

13H - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13G - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13F - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13E - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13D - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13C - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13B - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

13A - Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by ... Read More

Map data © 2019 Google

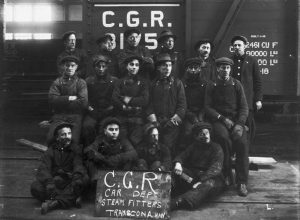

Grand Trunk Pacifi c Railway workers, c. 1915

CPR Weston Shops

Railway workers, c. 1920

The Weston Shops (CPR) and Labour Militancy

In 1919, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Canadian National Railway employed some 10,000 workers across Winnipeg and in nearby Transcona. ... Read More

11E - Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arr... Read More

11D - Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arr... Read More

11C - Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arr... Read More

11B - Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arr... Read More

11A - Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arr... Read More

Jewish radicals; Rose Alein (centre), elected in 1919 as school trustee from Independent Labour Party, 1906

Liberty Temple activists, c. 1926

Liberty Temple

Liberty Temple was home to the Winnipeg branch of the Arbeiter Ring (Workmen’s Circle), a progressive Jewish society that was dedicated to s... Read More

Ukrainian Labor Temple, 1983

Ukrainian Labor Temple, 2006

Editorial office, Ukrainian Labor Temple, post 1918

The Ukrainian Labor Temple (1918)

A building of great historical significance, the Ukrainian Labor Temple (ULT) was constructed largely by volunteer labour and with financial... Read More

St. John’s Telephone Exchange Building, 405 Burrows Avenue, 2013

Telephone Operators and Supervisors, 1919

St John’s Telephone Exchange Building (Winnipeg Housing Rehabilitation Corporation)

The rapid expansion of telephone networks in the early 20th century provided women with a new opportunity for employment. The industry appea... Read More

All People’s Mission, 470 Stella Avenue, c. 1920

Kindergarten class, All People's Mission, Maple Street Church, c. 1904

All Peoples’ Mission (CEDA - Community Education Development Association Winnipeg, Inc

This building housed one of several All Peoples’ Missions in the poorest immigrant neighbourhoods of Winnipeg’s North End. Most were run by ... Read More

Ethel Johns, Director of Nursing at Children’s Hospital, c. 1915

Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg, located at Aberdeen Avenue, Main Street and Redwood Avenue, c.1920

Nurses Residence, Children’s Hospital, 165 Aberdeen Avenue, c.1920 (still standing in 2019)

The 1918 Influenza Epidemic: Children’s Hospital and the Nurses School Residence

Winnipeg did not escape the ravages of the flu epidemic that swept much of the world in 1918. City officials reported 1,200 residents died f... Read More

Working class neighbourhood, c.1904

Children in poor housing, c.1916

Selkirk Avenue

Newcomers from central and eastern Europe lived in the least desirable housing, just north of the busy and noisy CPR railyards.... Read More

04C - Working-Class Housing

Drive along North End streets like Dufferin Avenue and Stella Avenue to see the many examples of houses occupied by working families in 1919... Read More

04B - Working-Class Housing

Drive along North End streets like Dufferin Avenue and Stella Avenue to see the many examples of houses occupied by working families in 1919... Read More

04A - Working-Class Housing

Drive along North End streets like Dufferin Avenue and Stella Avenue to see the many examples of houses occupied by working families in 1919... Read More

Point Douglas Ukrainian Labor Temple, 197 Euclid Avenue (constructed 1938), c. 1970

All People’s Mission, 119 Sutherland Avenue (Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre), c. 1910

Vulcan Iron Works, early 20th c.

Vulcan Iron Works and the Point Douglas Neighbourhood

Point Douglas changed rapidly after the railway cut through the community in the 1880s. The wealthy families living there, having pushed Ind... Read More

Canadian Pacific Railway Station and Royal Alexandra Hotel (left), 1909

Canadian Pacific Railway Station (Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg, Inc

Thousands of newcomers arrived at this site beginning in the late 1800s. The poorest among them were sent to immigration halls across Higgin... Read More

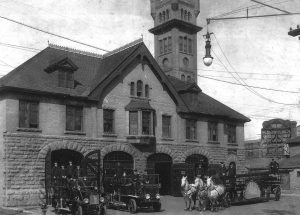

Winnipeg Fire Hall No. 3 (Maple Street), 1923

Winnipeg Fire Hall No. 3 (Maple Street), 1918

Winnipeg Fire Hall No

Winnipeg fire fighters were no strangers to labour activism in 1919. They had been lobbying for improved wages and hours of work for years.... Read More

Manitoba Legislative Building

The present Manitoba Legislative Building was partially open in 1919, but most government business was still conducted in the old Legislature located nearby, on the east side of Kennedy Street. The mass parades of pro- and anti-strike returned soldiers made their way past this site on their way down Broadway. The provincial government did not play a major role in the General Strike.

Premier Norris was reluctant to put his government between the strikers and the Citizens’ Committee, or between the federal and civic governments. After Bloody Saturday, Norris finally did meet with a delegation of strikers. He agreed to establish a Royal Commission to investigate labour conditions and the General Strike. This decision helped the Strike Committee in its decision to end the strike.

Also notable: Winnipeg Law Courts, 391 Broadway

Military tents, Fort Osborne Barracks, with the Manitoba Legislative Building under construction in background, 1919

Military tents, Fort Osborne Barracks, with the Manitoba Legislative Building under construction in background, 1919Archives of Manitoba

Fort Osborne Barracks

On June 21 (Bloody Saturday) Mayor Gray met with General Ketchen at the Fort Osborne Barracks. Gray instructed Ketchen to assemble all available men – from here and from the Minto Armoury (969 St. Matthews Avenue) to enforce his proclamation against street parades.

A crowd had gathered along Main Street to watch a pro-strike parade of returned soldiers. Ketchen acted immediately, sending soldiers from the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the Winnipeg Grenadiers, the Winnipeg Light Infantry and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders to patrol the streets.

The events of Bloody Saturday resulted from this intervention by the military and the Royal North West Mounted Police. The General Strike was one of the very few times in Canada’s history when soldiers were ordered to occupy a Canadian city and to police its own citizens.

Police on horseback at Fort Osborne Barracks, 1919

Police on horseback at Fort Osborne Barracks, 1919Archives of Manitoba

Broadway and the Manitoba Club

The Broadway area was in transition in 1919. Many residents had already moved to Crescentwood, but the area was popular with wealthy doctors, lawyers, bankers and businessmen who worked downtown.

The Manitoba Club was an exclusive, all-male club of the Anglo-Saxon elite. Winnipeg’s most influential business and political leaders met here. The club also served as a private, informal meeting place for the Citizens’ Committee in 1919. The nearby Vaughn Street Jail held labour leaders Helen Armstrong and John Queen during the strike. The jail and law courts played an important role in the post-strike trials.

Also notable: Vaughn Street Jail, 444 York Avenue at Memorial Boulevard

Manitoba Club, c. 1920

Manitoba Club, c. 1920Library and Archives Canada

James Street Labor Temple – Strike Headquarters

The James Street Labor Temple was the city hall of the labour movement. It was located on the city block where The Manitoba Museum now stands.

Union locals rented rooms here and the building housed the offices of the Winnipeg Trades and Labor Council (WTLC). Helen Armstrong, as President in the Women's Labor League, also had an office here. In early May in 1919, the Building Trades Council petitioned the WTLC for help in negotiations with their employers. They were not disappointed.

On May 13, the Western Labor News reported, “… never before in the history of Winnipeg has there been such a Trades Council session. It was tense, electric and determined. Every inch was jammed with a seething mass of trade unionists, men and women. Amid an oppressive hush,” the WTLC announced the results of its ballot for a city-wide sympathetic general  James Street Labor Temple, Strike Committee Headquarters

James Street Labor Temple, Strike Committee Headquarters

Archives of Manitoba

The meeting elected 300 members to a General Strike Committee, from which a 15-member Central Strike Committee was elected. This smaller committee met daily at the Labor Temple throughout the strike. It authorized those in essential services, like the police, to continue working and issued "Permitted by the Authority of the Strike Committee" posters to the corner stores in the North End to provide strikers with essentials like milk and bread. Mayor Gray and the Citizens’ Committee claimed that these posters represented the usurpation of constituted authority by the strikers. On June 17, the police raided the building, smashing windows, doors, and furniture. Union offices were trashed and documents seized.

For the strike leaders it was a demanding but exciting time. Each day began with a discussion of “…strike business in the morning,  Meeting Room 10, James Street Labor Temple

Meeting Room 10, James Street Labor Temple

Local 343, United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners

* Western Labor News, May 1919

Victoria Park - “Liberty Park”

“Vast Assembly in Victoria Park”*

The James Street Labor Temple was too small to hold the thousands of strikers and their supporters who gathered regularly for information on the strike.

Instead, mass meetings were held at nearby Victoria Park, located south of Pacific Avenue along the Red River. Victoria Park and the James Street Labor Temple were the heartbeat of the General Strike. Labour’s most crucial decisions on the strike were made at these sites. Ideals of participatory democracy permeated the city’s working classes in the spring of 1919.

On May 25, at Victoria Park, 5,000 strikers rejected the federal government’s ultimatum ordering telephone, post office, and fire department workers to return to their jobs. Two weeks later, Mayor Gray addressed a crowd at the park and “got a good hearing” when he informed the strikers that parades  Women and men at Victoria Park, June 1919

Women and men at Victoria Park, June 1919

Archives of Manitoba

The newly organized Labor Church was an integral part of the Victoria Park scene. Williams Ivens, a Methodist minister popular in the labour movement for his pacificism and anti-conscription campaigns  RE Bray, leader of the pro-strike returned veterans, June 13, 1919

RE Bray, leader of the pro-strike returned veterans, June 13, 1919

Archives of Manitoba, LB Foote Collection

Workers renamed Victoria Park “Liberty Park” in their conviction that their goals reached beyond the immediate issues of the day to dreams of equality, social justice, and a people’s democracy.

* The Strikers Own History, p 70

Walker Theatre (Burton Cummings Theatre)

The spirit of the One Big Union and the Russian Revolution roared from the stage of the Walker Theatre on Sunday afternoon, December 22, 1918. The Socialist Party of Canada organized this mass meeting.

Its members and other political radicals filled the 2,000-seat hall to capacity. The audience was politically left wing and remarkably multicultural, with workers from Anglo, Polish, Ukrainian, Hungarian, Jewish, Russian, and other cultural groups. Rousing speeches from prominent socialists including RB Russell, Dick Johns, George Armstrong, William Ivens, Fred Dixon, and Sam Blumenberg denounced inequality in Canadian society. They demanded freedom for labour activists who were detained during the war and an end to all government wartime emergency powers. Some spoke glowingly of the Russian Revolution and called upon the federal government to stop military aid to those opposing it. Other speakers predicted the end of capitalism and the rise of a new social order.

But few at this meeting, or throughout the city’s working-class neighbourhoods, saw Russia’s path to reform as the one for Canada. They believed that their

The Winnipeg Board of Trade Building (The Federal, or ‘Victory’ Building)

Today’s Federal Building stands on the site of the former Winnipeg Industrial Bureau Exposition Building, which housed the Winnipeg Board of Trade.

In 1919, it was the headquarters of the Citizens’ Committee and its newspaper, The Citizen. The Citizens’ Committee hung a large sign over the entrance declaring the building as its headquarters. On June 3, in one of the pro-strike demonstrations held in front of the building, a large group of angry war veterans tore the sign down.

Winnipeg Board of Trade Building, Citizens’ Committee Headquarters, 1919

Winnipeg Board of Trade Building, Citizens’ Committee Headquarters, 1919Archives of Manitoba, LB Foote Collection

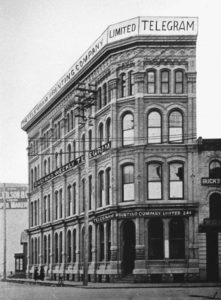

The Telegram Building

This building housed the Winnipeg Telegram, a daily newspaper which – like the Free Press and Tribune – joined the Citizens’ Committee in condemning the General Strike.

The Telegram referred to the strike as a deliberate, criminal and fantastic attempt to make a revolution. The Telegram combined its strike news with sensationalist reports on the Russian Revolution to help create a Red Scare in Winnipeg. The Telegram and other commercial newspapers declared the strike a revolution led by foreign “alien” agitators. In fact, the most prominent strike leaders were well-known trade unionists of British origin.

Telegram Building, 1903

Telegram Building, 1903Archives of Manitoba

The Women’s Labor League and the Labor Café (Royal Albert Arms Hotel)

Women's Labor League

The Winnipeg branch of the Women’s Labor League (WLL) provided essential leadership and support to women in the months leading up to, and during, the General Strike. It encouraged women to join the strike and helped those in need with rent payments and meals.

During the trials of the strike leaders, the WLL campaigned for the defendants’ freedom and raised funds for their defense.

Helen Armstrong, Katherine Queen, Gertrude Puttee, Lynn Flett, and a Mrs Webb held prominent roles in the WLL. Many more women, whose stories remain untold, joined them to make it a dynamic organization. The WLL supported women in unions, but dedicated great energy to organizing telephone operators, retail stores clerks and other non- unionized women. The WLL had three members on the Winnipeg Trades and  Members of the Winnipeg Women’s Labor League preparing relief packages for families of Nova Scotia Coal miners on strike, c. 1925

Members of the Winnipeg Women’s Labor League preparing relief packages for families of Nova Scotia Coal miners on strike, c. 1925

Archives of Manitoba

The Labor Café

The Labor Café set up by the WLL during the strike reflected the impressive solidarity that united Winnipeg’s working women and men in 1919. Many women – especially young strikers – had little support during this time. They were without strike pay and had meagre, if any, savings. The Labor Café provided thousands of women with free meals, offering soup and sandwiches made by volunteers in the kitchen, or donated by women throughout the working- class community. Men picketing downtown, or without other support, could also have meals here. William Ivens' collected $4,500 for the kitchen through his Labor Church. Other strikers – women and men – also raised funds to support the work of the café.

The Labor Café first opened at the Strathcona Hotel

(567 Main Street, at Rupert Avenue); moved to the Oxford Hotel (216 Notre Dame Avenue); and, finally, re-opened in the more spacious Royal Albert Arms Hotel.

Bloody Saturday

“June 21st, one of the blackest chapters in Canadian history…” * On the morning of June 21, pro-strike veterans assembled in front of city hall. They planned a “silent parade” to protest the arrest of the strike leaders in defiance of the mayor’s ban on demonstrations.

A huge crowd gathered to watch the parade.

Mayor Gray, informed by panicked officials that the situation in front of city hall was “out of control,” ordered the Royal North West Mounted Police and the military onto the streets. At 2:30 pm, 54 police on horses and 36 men in trucks lined up on Main Street facing north at Portage Avenue. Meanwhile, a streetcar drove south from north Main Street toward the crowds. Demonstrators believed the streetcar was driven by Citizens’ Committee volunteers. The crowd shoved the streetcar off its tracks, broke its windows and set it on fire.

The police walked their horses north on Main Street from Portage Avenue. They wore their distinctive red uniforms, but a few riders near the end of the troop wore army uniforms. The appearance of these soldiers enraged pro-strike veterans who jeered and booed them. The police turned around near city hall and headed south on Main towards their starting point. They were pelted with rocks and bricks.  Mounted Police charge into crowd at William Avenue, June 21, 1919

Mounted Police charge into crowd at William Avenue, June 21, 1919

Archives of Manitoba, LB Foote Collection

The police then rode north and charged back south again with their clubs in hand. A third police charge followed quickly upon the second. This time the police had clubs in one hand and revolvers in the other. The crowd stood back to let the police pass. But the police unexpectedly turned into the crowd at the corner of Main Street and William Avenue. Shots were fired. Several people fell wounded. An elderly bystander, Steve Schezerbanowes, was hit by police bullets. He died later from his wounds. The police brigade continued around behind city hall to re-emerge on Main Street at James Avenue. They headed south again on Main Street with revolvers still drawn. Mike Sokolowiski (Sokolowski), who the police claimed was throwing a brick, was shot and killed.

Two hundred “Special Police” emerged from the Rupert Street Police Station to cordon off Main Street.  “ Special Police” hose down crowds gathered in front of Bank of Montreal building at Portage and Main, June 21, 1919

“ Special Police” hose down crowds gathered in front of Bank of Montreal building at Portage and Main, June 21, 1919

Archives of Manitoba, LB Foote Collection

“Specials” pursued them. In the alley between Market Avenue and James Avenue, the undisciplined “Specials” cornered several hundred men, women, and children and attacked them with batons and other weapons. The crowd defended itself with bricks, bottles, and their bare fists. In ten minutes, 27 people were injured. The police, military and “Specials” proceeded to patrol downtown streets.

* Strike Bulletin, June 23, 1919

Citizens’ Committee Members and Residences

The Citizens’ Committee was organized as soon as the strike began by the residents of Winnipeg who opposed the unions’ position. Chaired by AK Godfrey, Past-President of the Board of Trade, and led by people such as AL Crossin, an insurance broker, and JE Botterell, a grain broker and member of the Board of Trade, the Citizens’ Committee widely publicized its intention to operate public utilities and other essential services with volunteers.

This was only one of its functions during the strike. Through its newspaper, The Citizen, the committee attempted to sway public opinion towards its own conviction that sympathy strikes were unnecessary, expensive, and potentially dangerous to public and private property. The Citizen portrayed the General Strike as a Bolshevik Revolution led by foreign revolutionaries. These sentiments were also expressed by Crescentwood residents like Councillor John K Sparling and AJ Andrews, lawyer and leading member of the Citizens’ Committee. The Citizens’ Committee’s position that the city should not negotiate with the strikers held sway on city council. The Citizens’ Committee was secretive about its membership. No formal

Residences of Citizens' Committee

13A

Alfred Joseph Andrews, lawyer

749 Wellington Crescent (demolished)

13A

13B

John Esterbrooke Botterell, merchant

254 Wellington Crescent

13B

13C

William Henry Carter, businessman

251 Harvard Avenue

13C

13D

Thomas Russ Deacon, owner, Manitoba Bridge and Iron Works and Mayor of Winnipeg

144 Yale Avenue

13D

13E

Alvin Keyes Godfrey, grain merchant

144 Kingsway

13E

13F

General Huntley Douglas Brodie Ketchen, military officer and later, politician

111 Nassau Avenue

13F

13G

WB Moore, Winnipeg Board of Trade Secretary

785 Dorchester Avenue

13G

13H

Isaac Pitblado, lawyer

523 Wellington Crescent

13H

Winnipeg Fire Hall No. 3 (Fire Fighters Museum of Winnipeg)

Winnipeg fire fighters were no strangers to labour activism in 1919. They had been lobbying for improved wages and hours of work for years.

These concerns and the fear that new recruits would lose their jobs to returning soldiers led to the formation of the Winnipeg Firemen’s Union in 1916. When civic workers struck in 1918, fire fighters joined in. Most city workers won modest wage increases, union recognition and the right to strike. Fire fighters were refused this right. Strike action could mean dismissal.

Despite this threat, fire fighters voted overwhelmingly to support the General Strike. At the same time, they pledged to provide full service where human life was in danger. Civic authorities rejected this offer. On May 26, Winnipeg City Council dismissed fire fighters and all other civic employees who refused to return to work. It passed resolutions prohibiting fire fighters from joining international unions and participating in sympathy strikes.

The Citizens’ Committee advertised for replacements and hired 350 anti-strike volunteers. On Bloody Saturday, these “volunteers” used fire hoses to douse protesters. Equipment from the Maple Street fire hall was sent to extinguish the street car fire.

In the days to come, 54 of the 204 firefighters  Winnipeg Fire Hall No. 3 (Maple Street), 1918

Winnipeg Fire Hall No. 3 (Maple Street), 1918

Fire Fighters Historical Museum of Winnipeg, Inc.

Canadian Pacific Railway Station (Aboriginal Centre of Winnipeg, Inc.)

Thousands of newcomers arrived at this site beginning in the late 1800s. The poorest among them were sent to immigration halls across Higgins Avenue.

These buildings provided offices for immigration agents and temporary accommodation to immigrants with no other options. Disease flourished in these crowded halls. Other newcomers stayed at nearby hotels and boarding houses, or were met by family members and taken to their homes.

By contrast, the railway’s Royal Alexandra Hotel (Higgins and Main) provided wealthy travelers with splendid accommodation. Federal government authorities stayed here during the strike and held meetings here with Citizens' and Strike Committee leaders.

Canadian Pacific Railway Station and Royal Alexandra Hotel (left), 1909

Canadian Pacific Railway Station and Royal Alexandra Hotel (left), 1909Western Canada Pictorial Index

Vulcan Iron Works and the Point Douglas Neighbourhood

Point Douglas changed rapidly after the railway cut through the community in the 1880s. The wealthy families living there, having pushed Indigenous peoples out of the area years before, moved to the newer, quieter neighbourhoods of south end Winnipeg.

Industries crowded into Point Douglas to take advantage of the railway for shipping and receiving. Factories produced farm implements, paints, liquor, beds, wagons and carriages. Hundreds of workers were employed.

Few of those living in Point Douglas – or in other working-class neighbourhoods – owned their homes. Families usually rented accommodation,  All People’s Mission, 119 Sutherland Avenue (Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre), c. 1910

All People’s Mission, 119 Sutherland Avenue (Manitoba Indigenous Cultural Education Centre), c. 1910

Western Canada Pictorial Index

The Vulcan Iron Works, which manufactured parts for the railways, was one of Winnipeg’s largest metalworking shops. Its buildings stretched along the railway tracks for several city blocks. Vulcan employees worked longer hours, earned lower wages, and faced poorer working conditions than the unionized metal trades workers who were employed directly by the railways. Before the First World War, metal trades workers at Vulcan Iron works, Manitoba Bridge and Dominion Bridge lost several bitter fights with these companies over the right to have a union. Workers’ discontent escalated during the war. Employers demanded ever greater production, while inflation eroded the workers’ incomes. Skilled workers at Vulcan, Manitoba Bridge, and Dominion Bridge struck again in 1917 and 1918, demanding union recognition and improved wages and working conditions. But the employers prevailed in these disputes. They hired strike breakers and brought in a detective agency to intimidate the workers. They backed up these tactics with court injunctions against picketing of their premises.

Determined to win union recognition, workers struck once again on May 1, 1919. This time, the strikers had the full support of Winnipeg’s powerful Metal Trades Council. The Council represented and bargained for 19 craft unions in the city’s main railway shops. Its members were determined to secure a victory for their non-unionized brothers. But once again, the employers fought hard against unionization. Neither side was willing to compromise. The Metal Trades Council  Vulcan Iron Works, early 20th c.

Vulcan Iron Works, early 20th c.

Archives of Manitoba, LB Foote Collection

Working-Class Housing

Drive along North End streets like Dufferin Avenue and Stella Avenue to see the many examples of houses occupied by working families in 1919.

These streets, with their often tiny houses pressed together on 25 foot lots, are typical of the homes that flanked the north and south sides of the CPR railyards stretching from Point Douglas to Keewatin Street. Workers lived in these neighbourhoods because they were located near their place of work and, often, this was the only accommodation they could afford.

The rail yards and factories nearby made life here difficult. Smoke filled the air and soot blackened furnishings and windows.  Tenement housing in North End Winnipeg, early 20th c.

Tenement housing in North End Winnipeg, early 20th c.

Western Canada Pictorial Index

Corner of King Street and Dufferin Avenue, 1904

Corner of King Street and Dufferin Avenue, 1904Archives of Manitoba

Working-Class Housing

04A

Children’s Hospital of Winnipeg

Aberdeen Avenue, Main Street and Redwood Avenue

04A

04B

Nurses Residence, Children’s Hospital

165 Aberdeen Avenue (still standing in 2019)

04B

04C

Ethel Johns, Director of Nursing at Children’s Hospital

165 Aberdeen Avenue

04C

Selkirk Avenue

Newcomers from central and eastern Europe lived in the least desirable housing, just north of the busy and noisy CPR railyards.

Over 80 percent of Winnipeg’s Jewish and Slavic families lived here in 1919.

Selkirk Avenue was the retail and cultural focus of the new neighbourhood. Confectioneries, butcher shops, grocery stores, banks, real estate agencies, loan offices, theatres, and meeting halls lined the street. German, Jewish, Polish, Ukrainian, and English-language community newspapers kept residents up to date on local news and events in their homelands. Mutual benefit societies like the North End Relief Association, the Hungarian Kossuth Sick Benefit Association, and the United Hebrew Charities offered companionship and financial assistance to those in need.

The North End, with its diversity of languages, religions, dress, and culture, stood in sharp contrast to other  Working class neighbourhood, c.1904

Working class neighbourhood, c.1904

Archives of Manitoba

Not everyone in Winnipeg found the diversity of Selkirk Avenue to their liking, however. Many newcomers experienced intense discrimination. They heard their neighbourhoods belittled by outsiders as “the foreign quarter,” “CPR town,” or “New Jerusalem.”

Children in poor housing, c.1916

Children in poor housing, c.1916Archives of Manitoba

The 1918 Influenza Epidemic: Children’s Hospital and the Nurses School Residence

Winnipeg did not escape the ravages of the flu epidemic that swept much of the world in 1918. City officials reported 1,200 residents died from influenza that fall.

Thousands of others became ill. The flu affected families throughout the city. Working-class neighbourhoods faced the greatest devastation, and immigrants suffered the most. Having wealth meant better living conditions and sanitation, which limited the spread of disease. It also meant that those who did become ill had greater access to health care. The flu killed entire households, orphaned children, and made single parents of many adults. Working class and immigrant men and, especially, women faced a difficult future. They lacked the resources the city’s wealthier residents had to improve their lives.

Influenza fueled the momentum toward the social upheaval of 1919. Mutual assistance within working-class neighbourhoods during the crisis deepened social solidarity, while the slow and inadequate response of government left people angry. The state’s unwillingness to involve labour in decision making on public health issues also frustrated workers. Bans on public meetings in the last days of the epidemic led many to conclude the restrictions were meant to frustrate labour organizing.

Working-class and immigrant women played a crucial role caring for the sick. Much of this work went unnoticed. Male labour leaders responded in a traditional way, assuming women would serve as mothers and caregivers while men acted as breadwinners. Even the many politically empowered, middle-class women who volunteered during the crisis were unable to shake the patriarchal norms of the era.

Children’s Hospital cared for youngsters who became sick, or whose parents were ill or had died during the epidemic. The hospital’s Director of Nursing, Ethel Johns, was praised by her bosses for her “efficient, innovative and aggressive” running of the facility. They credited her  Ethel Johns, Director of Nursing at Children’s Hospital, c. 1915

Ethel Johns, Director of Nursing at Children’s Hospital, c. 1915

Winnipeg Health Sciences Centre Archives

* Harry Medovy, A Vision Fulfilled: The Story of the Children's Hospital of Winnipeg (1979), p. 136-137

All Peoples’ Mission (CEDA - Community Education Development Association Winnipeg, Inc.)

This building housed one of several All Peoples’ Missions in the poorest immigrant neighbourhoods of Winnipeg’s North End. Most were run by the Methodist Church but Anglican and Presbyterian missions also operated nearby.

Committed to improving social conditions for immigrants, these churches accompanied their relief efforts with a strong cultural message. Mission programs emphasized Anglo-Saxon values and Protestant Christian beliefs. Activities ranged from providing charitable donations, like food hampers, to offering Sunday school lessons, advice on sanitation, and “Fresh Air” summer camps for the children of the poor. Health care for immigrant women and children was, perhaps, the most important contribution of the missions. JS Woodsworth, who in 1933 was elected the first leader of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, directed the work of the Stella Avenue Mission from an adjoining house between 1907 and 1913. At the beginning of the First World War, he left Winnipeg and did not return until the General Strike was in progress.

All People’s Mission, 470 Stella Avenue, c. 1920

All People’s Mission, 470 Stella Avenue, c. 1920Western Canada Pictorial Index

St John’s Telephone Exchange Building (Winnipeg Housing Rehabilitation Corporation)

The rapid expansion of telephone networks in the early 20th century provided women with a new opportunity for employment. The industry appealed to young women. It advertised clean working conditions, an all-female workplace, and better wages than factory and retail jobs.

However, conditions were not as advertised. Long hours with few breaks, low wages, and constant supervision – to force the women to work harder and not use time to speak with one another – soon frustrated many operators. By 1918, most telephone operators were employed by the Manitoba Government Telephone System. That year they joined other government employees in a general strike that set the stage for the confrontation of 1919.

In May 1919 most operators, in Winnipeg and in the many rural telephone exchanges, left their switchboards and joined the General Strike. This meant there was no telephone service in Manitoba for most of the first week of the strike. The Citizens’ Committee arranged for replacement workers to re-open the telephone exchanges and paid them much more than the striking operators. Some services were provided but the system remained disrupted until the strike was over. Operators who struck for the duration of the General Strike were fired and blacklisted.

St. John’s Telephone Exchange Building, 405 Burrows Avenue, 2013

St. John’s Telephone Exchange Building, 405 Burrows Avenue, 2013Photo: Sharon Reilly

The Ukrainian Labor Temple (1918)

A building of great historical significance, the Ukrainian Labor Temple (ULT) was constructed largely by volunteer labour and with financial donations from members of the city’s progressive Ukrainian community.

A wonderfully preserved community hall, rich in history, it is a must see on the strike tour.

Many mutual benefit societies flourished in Winnipeg in the early 1900s. They began as voluntary organizations founded on the efforts of  Ukrainian Labor Temple, 2006

Ukrainian Labor Temple, 2006

Association of United Ukrainian Canadians Archive

Other ethnic associations offered similar companionship and assistance to immigrant communities. Liberty Temple, for example, was established by Jewish radicals. Both the Ukrainian Labor Temple and Liberty Temple were raided by the police on the night of June 16 –17. The ULT printing presses were smashed and books and files were seized and used to claim evidence of a conspiracy during the trials of the strike leaders.

Liberty Temple

Liberty Temple was home to the Winnipeg branch of the Arbeiter Ring (Workmen’s Circle), a progressive Jewish society that was dedicated to social change and mutual aid. It also promoted the Yiddish language and culture.

Committed to working-class solidarity that stretched beyond ethnic boundaries, the society hosted many intense debates among left-wing Jewish political groups.

The 1919 strike was strongly supported by Jewish radicals. Three of these individuals served on the Strike Committee – AA Heaps, a labour politician; and Max Tessler and M Temenson of the Metal Workers Union. The Israelite Press carried scathing indictments of the Citizens’ Committee. Liberty Temple served as an information centre on the strike. Anti-strike campaigns targeted Jewish strikers with a barrage of anti-immigrant and antisemitic attacks. On June 17, Liberty Temple was raided by the police. Jewish homes were ransacked, and three men were arrested and faced with the possibility of immediate deportation – Samuel Blumenberg, Michael Charitinoff, and Moses Almazov. A Jewish Workers’ Committee was formed to organize a Strike Relief Fund in their support.

Jewish radicals; Rose Alein (centre), elected in 1919 as school trustee from Independent Labour Party, 1906

Jewish radicals; Rose Alein (centre), elected in 1919 as school trustee from Independent Labour Party, 1906Jewish Historical Society of Western Canada

Arrest of the Strike Leaders, June 17

The arrest of the strike leaders on June 17 was dramatic. At 2:00 am eight police cars swept down on the homes of the men who were to be arrested. Each car carried three armed police officers.

They roused the suspects from their sleep and took them into custody. The police raided the James Street Labor Temple, surrounding it with 500 soldiers and members of the Royal North West Mounted Police (RNWMP). Police also raided the Ukrainian Labor Temple and offices of the Western Labor News. RB Russell, John Queen, George Armstrong, Roger Bray, AA Heaps, William Ivens, Bill Pritchard, and Dick Johns were charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government by force. These men were of British origin and were prominent leaders in the local and regional labour and socialist movements. They had gained the respect of Winnipeg’s working class citizens through many years of hard work, and their supporters would come to their aid after the arrests.

Four more men were apprehended by the police on June 17 –  Arrested strike leaders at Vaughn Street jail, fall 1919

Arrested strike leaders at Vaughn Street jail, fall 1919

Library and Archives Canada

Residences of the Arrested Strike Leaders

11A

Abram Albert (AA) Heaps, furrier

562 Burrows Avenue (now demolished)

11A

11B

William Ivens, Labor Church minister and journalist

309 Inkster Avenue

11B

11C

John Queen, cooper

317 Alfred Avenue

11C

11D

Robert Boyd (RB) Russell, machinist

1415 Ross Avenue

11D

11E

Richard J. (Dick) Johns, machinist

256 Isabel Street (now demolished)

11E

The Weston Shops (CPR) and Labour Militancy

In 1919, Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and Canadian National Railway employed some 10,000 workers across Winnipeg and in nearby Transcona. The railways’ operations were complex.

All kinds of skilled workers and many more unskilled labourers were needed to maintain the rail system, run the trains, and handle the huge volume of freight and passengers that passed through Winnipeg. The Weston Shops, one of several worksites operated by the railways in the city, hired hundreds of machinists, moulders, plumbers, pipefitters, and other skilled workers. Large numbers of semi-skilled workers and labourers also found work here. The men working in these shops repaired the companies' steam engines, and freight and passenger cars. They forged steel for the rails, and did the many other jobs essential to the successful operation of the railway. Only a few original buildings remain from this era.

Long hours of labour, dirty and noisy working conditions, and low wages in these industries prompted the skilled workers to organize into 19 different craft unions before the First World War. During the war, these unions  Grand Trunk Pacifi c Railway workers, c. 1915

Grand Trunk Pacifi c Railway workers, c. 1915

Western Canada Pictorial Index

In spring 1919, Russell and Johns were also working, along with other socialist leaders across Canada, to create the One Big Union (OBU). An extension of the industrial union model emerging in the railway shops, the OBU was to include all Canadian workers – regardless of their skill, gender, race or ethnicity – in a  CPR Weston Shops

CPR Weston Shops

Archives of Manitoba

The 1919 illuminated video is brimming with captivating historic images and news articles that show the development of Winnipeg’s architecture and social uprising. Discover the origins of what caused civil unrest which led citizens to start the 1919 General Strike.

Learn about the historic areas and people that helped shape the social democratic movement. Compare historic landmarks from the 20th century to modern day.